DIVas verksamhet |

Hur kan jag tala med mitt barn om rasism?

Online diskussionskväll om rasism och föräldraskap tisdag 21.4.2026 kl 17.30-19.00Läs mera »

09.03.2026 kl. 16:20

DIVa och Ad Astra bjuder in till frukost och diskussion!

Vi inleder veckan mot rasism med en gemensam frukost och diskussion om trygghet i en polariserad värld både ur nyare och äldre minoriteters perspektiv.Läs mera »

09.03.2026 kl. 12:57

Att göra skillnad - Antirasistiskt arbete med unga

Jobbar du med unga och är intresserad av hur du kan jobba antirasistiskt? Anmäl dig till seminariet som ordnas 6.5.2026 i Vasa.Läs mera »

26.02.2026 kl. 13:24

DIVa har en ny verksamhetsledare

Vi välkomnar DIVas nya verksamhetsledare Laura Louhe som från och med årsskiftet jobbar 40% för föreningen.Läs mera »

26.02.2026 kl. 12:32

Rapport för ECRI

DIVa rf och Ad Astra rf har färdigställt en rapport för Europeiska kommissionen mot rasism och intolerans (ECRI) som undersöker förekomsten av rasism, mobbning och diskriminering i finska skolor. Läs mera »

13.12.2024 kl. 14:00

Seminariet "Trygg på Dagis"

Seminariet riktar sig till småbarnspedagoger och andra som möter barn både på arbetstid och till vardags, och som vill lära sig mera om rasism och antirasism i en dagiskontext.Läs mera »

20.05.2024 kl. 14:56

Men det gäller väl inte oss?

En interaktiv föreläsning om varför just du också behöver göra något åt rasism.

Tisdagen den 12 september 2023 kl. 17–19

Läs mera »

25.04.2023 kl. 10:15

Rasismen ökar i finlandssvenska skolor

Rasismen har samtidigt blivit råare än vad den varit tidigare, säger rektor Agneta Torsell.Läs mera »

24.03.2023 kl. 11:00

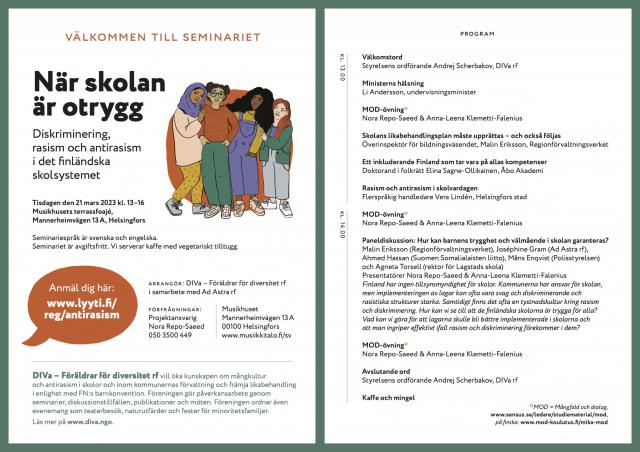

När skolan är otrygg

Välkommen till seminariet "Diskriminering, rasism och antirasism i det finländska skolsystemet" tisdagen den 21 mars 2023 kl. 13–16Läs mera »

02.03.2023 kl. 11:27

InformatIonspaket för föräldrar

Den här broschyren är en hjälpreda när det brister. Se den som ett brev från förälder till förälder, utan mellanhänder.Läs mera »

01.03.2023 kl. 20:37